The Sydney Tar Ponds are one of the largest environmental disasters that Canada has ever known. Located on the eastern shore of the Sydney Harbour in Sydney – now known as the Cape Breton Municipal Council – the ponds formed at the tidal mouth of Muggah Creek, which is a long-running freshwater stream that feeds into the harbour. The reason for their contamination: steel production.

The Sydney Steel Corporation is behind one of Canada’s biggest environmental disasters. This is their story.

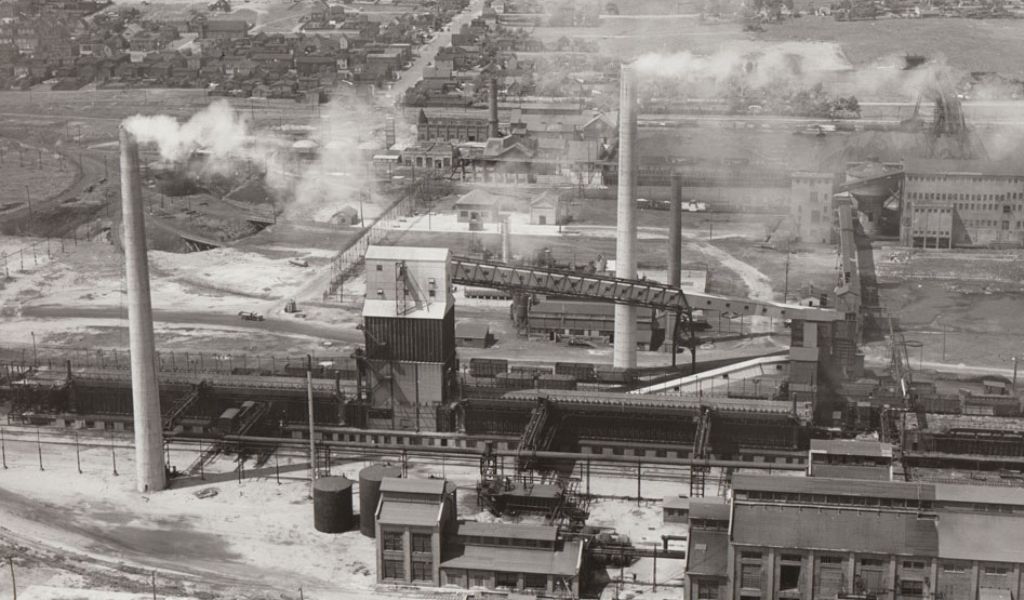

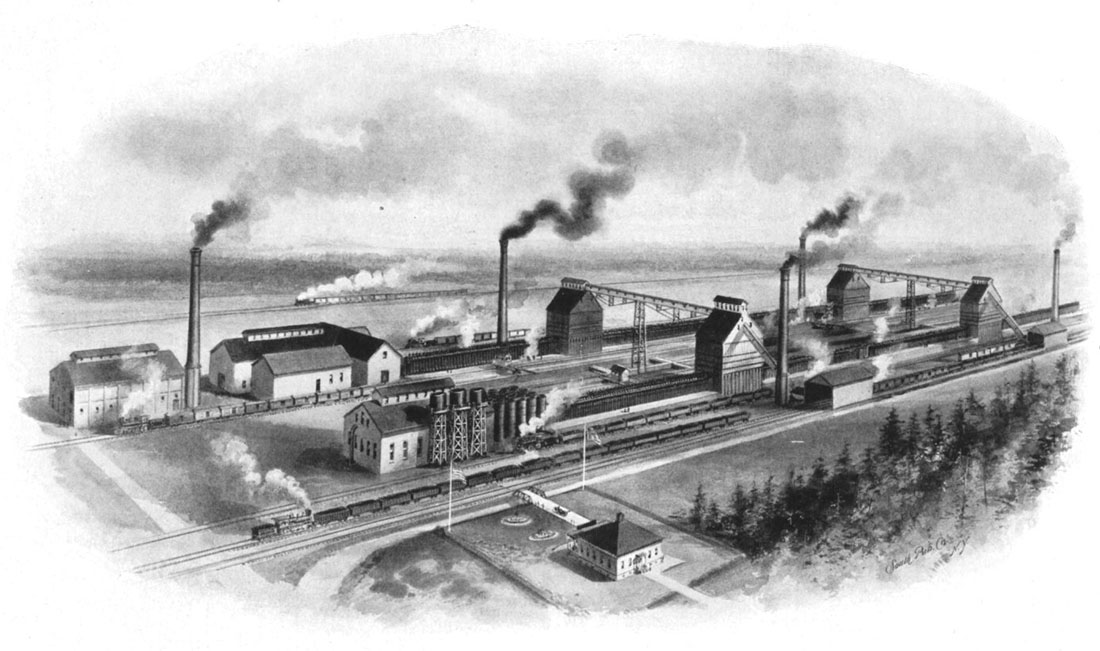

At the very end of the 19th century, American investors formed the Dominion and Iron Steel Company LTD (DISCO) and began large scale steel production in Wintering Cove, Sydney. The area was ripe for steel production, with iron ore, limestone and coal at hand in troves. It also has a good harbour for shipping and a good fresh water supply. Within a decade of opening, the steel mill was producing 800,000 tonnes of pig iron and 900,000 tonnes of crude steel – nearly half of Canada’s steel production. It was also one North America’s largest steel production company.

The mill remained prosperous for over a century, right up until 1967 when then-owners, the Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation (DOSCO), announced the closure of the mill. In fear of poor economic prospects that this would yield for the region, the Nova Scotian government took possession of the mill, renaming it the Sydney Steel Corporation (SYSCO).

During production throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, operations had dire consequences for the surrounding environment – in particular the wetlands and harbour adjacent to the plant. The facility was situated directly adjacent to and north of the coke oven operations. These coke ovens produced a huge amount of hazardous materials that flowed freely into the subsequently named Tar Ponds.

Throughout the 1970s, as environmental activism began to take heed, concerns for the damage that these mills were causing had reached new heights. Environmental groups would consistently uncover evidence that the government didn’t know the damage that the mills were causing to the environment, or they did and were turning a blind eye. In 1980s, scientists discovered polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the lobster caught in Sydney harbour – a direct result of contamination from the Tar Ponds.

Insistent pressure from various sources caused the steel mill to cease operations in 1988, when the Sydney Steel Corporation turned into an electric arc manufacturer. Industrial production ceased altogether in 2000.

In 1986, Canada has signed an agreement to dredge the Tar Ponds and pump the sludgy sediment to a nearby plant for combustion. After many delays the plant was finally completed, however, the sludge proved too thick to pump through the pipes. Because of this, among many other problems including the sludge proving too toxic to be handled by the incinerator plant, the project was abandoned in 1995.

Nearly ten years later, in 2004, the Canadian and Nova Scotian governments signed a decade-long, $400M contract to clean up the Tar Ponds and the area around the coke ovens. Carl Buchanan, chairman of the Joint Action Group (JAG) in charge of the solicitation process for cleaning up the Tar Ponds, summarised the task: “This is going to be the most complex environmental cleanup ever undertaken in this country, and maybe anywhere. It’s never been done on this scale, and right in the middle of a city.”

The first phase of the project was completed in mid-December 2009. The project was finally completed in 2013, which saw the opening of Harbourside Commercial Park and Open Hearth Park, which now sit up on the old site of the Sydney Steel Corporation.